This is a paper I wrote for my Wittgenstein class. I liked it enough to put it here; I think there are some good ideas in it– I wish I had more time to expand some of them, and refute some of the things I read in others, but like all assignments, this had a deadline.

I. Wittgenstein and Music

Ludwig Wittgenstein came from a family of musicians; as Ray Monk puts it, “The extent to which the Wittgensteins venerated music is perhaps hard for us to appreciate today” (Monk, pg. 13). Though he didn’t play an instrument until later in life (the clarinet), he was surrounded by, and grew up amongst musicians and composers of prodigious talent. It’s unsurprising, therefore, to see musical examples used throughout his philosophy, one of the most famous examples used to illustrate the picture theory in the Tractatus.

4.014 The gramophone record, the musical thought, the score, the waves of sound, all stand to one another in that pictorial internal relation, which holds between language and the world.

To all of them the logical structure is common.

(Like the two youths, their two horses and their lilies in the story. They are all in a certain sense one.) 1

4.0141 In the fact that there is a general rule by which the musician is able to read the symphony out of the score, and that there is a rule by which one could reconstruct the symphony from the line on a gramophone record and from this again—by means of the first rule—construct the score, herein lies the internal similarity between these things which at first sight seem to be entirely different. And the rule is the law of projection which projects the symphony into the language of the musical score. It is the rule of translation of this language into the language of the gramophone record.

It’s a fascinating notion; but one which relies heavily on a kind of precision in interpretation we don’t really see, even in score-based performances, which offer variations in tempo, dynamics, etc. And it would not have survived an encounter with graphical scores.

II. A Few Notes on Graphical Scores.

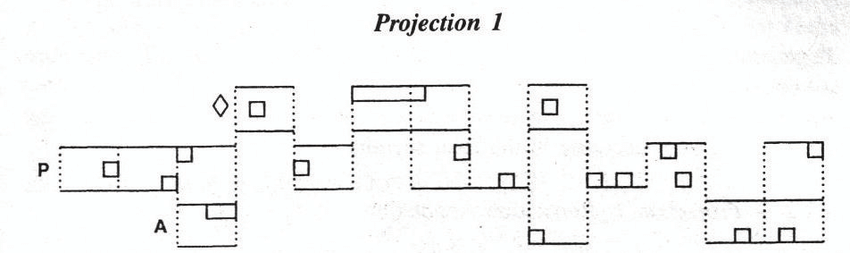

With the rise of the avant-garde in the 1950s, composers sought new ways of expression; “standard” musical structures, instrumentation, and in the extreme case of Cage’s 4’33”, even playing instruments became optional. It’s doubtful Wittgenstein would have had time for much of this music (and even some modern aesthetic philosophers, like Scruton, are very quick to dismiss it (Scruton, p. 16)). Wittgenstein, for example, thought Mahler’s music “worthless” (Marchesin). One can’t imagine him sitting through something like Feldman’s Projection I without objections. Here is its score, and you can listen to a realization of it here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OZcRU3mrDM8.

This is for a solo cello— performed at 60 beats per minute, each box represents a quarter note, and the three rows are relative pitch and a specific articulation. Actual pitch is left up to the performer. This means that the “picture”, in Wittgenstein’s terms does not represent a state of affairs, but rather a set of states of affairs, numbering in the billions; all of which are “true” depending on what is played. In other words, the score can be turned into a performance, the performance into a recording, but the recording cannot be turned back into the score. You could create a standard notated score from any given performance, but it is not the score. The logical structure ceases to be common; breaking one of Wittgenstein’s propositions.

Wittgenstein himself came to realize that the idea of everything having a “logical form” was an error; famously Piero Sraffa asked “what is the logical form of this”, making the gesture of flicking fingers from under the chin. It is, of course more complex than that, Sraffa proved to be an excellent foil for Wittgenstein, making him rethink his work over time (Albaini, pp 2-3).

Feldman’s, and other graphical scores frequently contain parts of ‘standard’ notation; specifying tempo, instrumentation, etc. They represent a kind of ‘partial logic’. We now turn our attention to one of the most radical graphical scores, Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise, which was directly inspired by Wittgenstein and his shift in thought.

III. Treatise, the Tractatus, and Philosophical Investigations

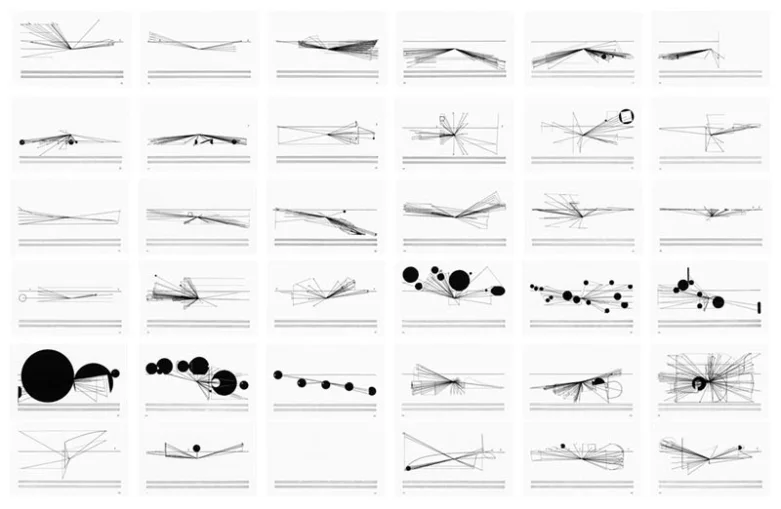

Treatise is a massive work. It’s 192 pages of graphical score- here are some sample pages from it:

It contains no notes on performance, instrumentation, or tempo— it is rarely performed completely (at a minute per page, which is fairly fast, it would take just under three and a half hours). In general, performers decide what the score ‘means’ and interpret it on basis of a shared understanding of the symbology. Cardew wrote a few notes on Treatise in a separate work called Treatise Handbook. He mentions Wittgenstein five times; and although the title of the work appears to be an allusion to the Tractatus (Brian Dennis notes some similarities to the structure of Treatise and the Tractatus, by comparing the visual elements and layout to the structure of arguments in the Tractatus, but the author of this paper found it to be quite a stretch), it would appear that Cardew was much more interested in Wittgenstein’s later work. “In his later writing Wittgenstein has abandoned theory, and all the glory that theory can bring on a philosopher (or musician), in favour of an illustrative technique.” and “Wittgenstein: “And if e.g. you play a game you hold by its rules. And it is an interesting fact that people set up rules for pleasure, and then hold by them” . (Cardew, Treatise Handbook). These appear to be clear allusions to Philosophical Investigations; both the reference to ‘games’ and ‘rule following’ and the ‘illustrative technique’.

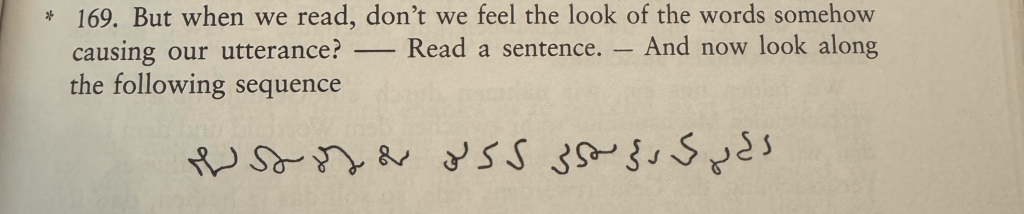

Note that Wittgenstein occasionally makes use of “nonsense symbols” in Philosophical Investigations. Consider this excerpt from 169:

This is the “illustrative technique” that Cardew mentions— here Wittgenstein is (to paraphrase Baker and Hacker pp. 342-346) attempting to shed light on the nature of reading and “being guided”. As Wittgenstein writes in section 175 – 176 “Make some arbitrary doodle on a bit of paper.——And now make a copy next to it, let yourself be guided by it….while I am being guided everything is quite simple, I notice nothing special; but afterwards, when I ask myself what it was that happened, it seems to have been something indescribable. Afterwards no description satisfies me…When I look back on the experience I have the feeling that what is essential about it is an ‘experience of being influenced’, of a connexion…” The experience is something you *do*, not something that *happens to you* (Baker and Hacker, p. 348).

These would appear to be far closer to Cardew’s notions in creating Treatise than anything specifically from the Tractatus. We allow ourselves, as interpreters, to use the lines, circles, and other elements in Treatise as a guiding element; we make up the rules of the game, we follow them. It is, if performed with intention, an activity much the way that Wittgenstein regarded all of philosophy as an activity. It is a language game in which the rules are decided upon by the players at one moment, and which exists only as long as the players stick by the rules and ceases to be understood the moment they stop.

Wittgenstein’s own relationship with music is quite a complex one. Primarily, in Philosophical Investigations he suggests that understanding a musical theme is akin to understanding a sentence (Proposition 527 in Philosophical Investigations). Marchesin suggests, however, that rules (such as those of a language game) “cannot capture expressivity of musical themes”. Treatise would appear to be an attempt to create only that expressivity; the rules created by the performers may never be known to the audience, looking at the score does not provide us with guidance as to what they are doing. It’s an extension of 530 of the Philosophical Investigations “There might also be a language in whose use the ‘soul’ of the words played no part. In which, for example, we had no objection to replacing one word by another arbitrary one of our own invention.” Marchesin notes that music is “not a means of communication” and notes that different people may interpret the same piece of music in a different fashion. Here, the music itself, by design, will never be interpreted the same way, even by the players; even agreeing on the same set of rules to govern the interpretation of the score will result in different outcomes.

IV. Conclusion

Treatise remains a fascinating piece of work. It is interesting to note that, like Wittgenstein retracted parts of the Tractatus, Cardew would go on to repudiate his own work. Cardew became a revolutionary Marxist, and came to see his prior work as somehow supporting the bourgeoise; he would denounce his prior teachers as “serving imperialism”, and attempted to steer his music in some way to supporting the worker. (Lipman). But also like the Tractatus, his refutation of the work does not change its nature. Certainly, parts of the Tractatus are still a part of modern philosophy (especially the use of truth tables). And the radical notions that Treatise puts forward about the nature of music and interpretation are still being felt in the world of music, especially avant-garde music today.

Philosophically, its direct connections to Wittgenstein’s later work are of interest; the seeking to create a game with rules only understood by the players, a language game with a single piece of surface instruction: interpret. It is, ultimately aligned with the Wittgensteinian notion of activity; Treatise is something you do, a thing that if approached in the right spirit, may just serve to help you throw away the ladder, if only musically.

1. As an aside, this “two youths, lillies” reference comes from a frighteningly obscure folk tale, one not even recognized by most Germans. (Pfeifer) The tale is called “The Golden Lads” and is weirdly complicated. It can be read here: https://www.worldoftales.com/fairy_tales/Andrew_Lang_fairy_books/Green_fairy_books/The_Golden_Lads.html

Works Cited

Albani, P. Sraffra and Wittgenstein: Profile of an Intellectual Friendship History of Economic Ideas, 6(3), 151–173. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23722611

Baker, GP and Hacker, PMS Wittgenstein: Understanding and Meaning : Part II Exegesis 1-184 Wiley-Blackwell

Cardew, Cornelius Treatise Edition Peters

Cardew, Cornelius Treatise Handbook Edition Peters

Dennis, Brian Cardew’s ‘Treatise’ (mainly the visual aspects) Tempo, New Series, No. 177 (Jun., 1991), pp. 10-16 http://www.jstor.org/stable/945927

Lipman, Samuel. Review of Stockhausen Serves Imperialism Commentary, Dec. 1975 retrieved https://www.commentary.org/articles/samuel-lipman/stockhausen-serves-imperialism-by-cornelius-cardew/

Marchesin, M. Wittgenstein’s Account of Music and its Comparison to Language: Understanding, Experience and Rules. Philos Inv, 45: 490-511. https://doi.org/10.1111/phin.12342

Monk, Ray Ludwig Wittgenstein : The Duty of Genius Penguin Books

Pfefier, Karl Notes on a Cold Case: Wittgenstein’s Allusion to a Fairy Tale in Radford, C. (1988). WITTGENSTEIN AND “FAIRY TALES.” Merveilles & Contes, 2(2), 106–110. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389968

Scruton, Roger The Aesthetics of Music Clarendon Press

Wittgenstein, Ludwig Tractatus Logico-Philisophicus Damion Searls, Translator Liveright Publishing

Leave a comment